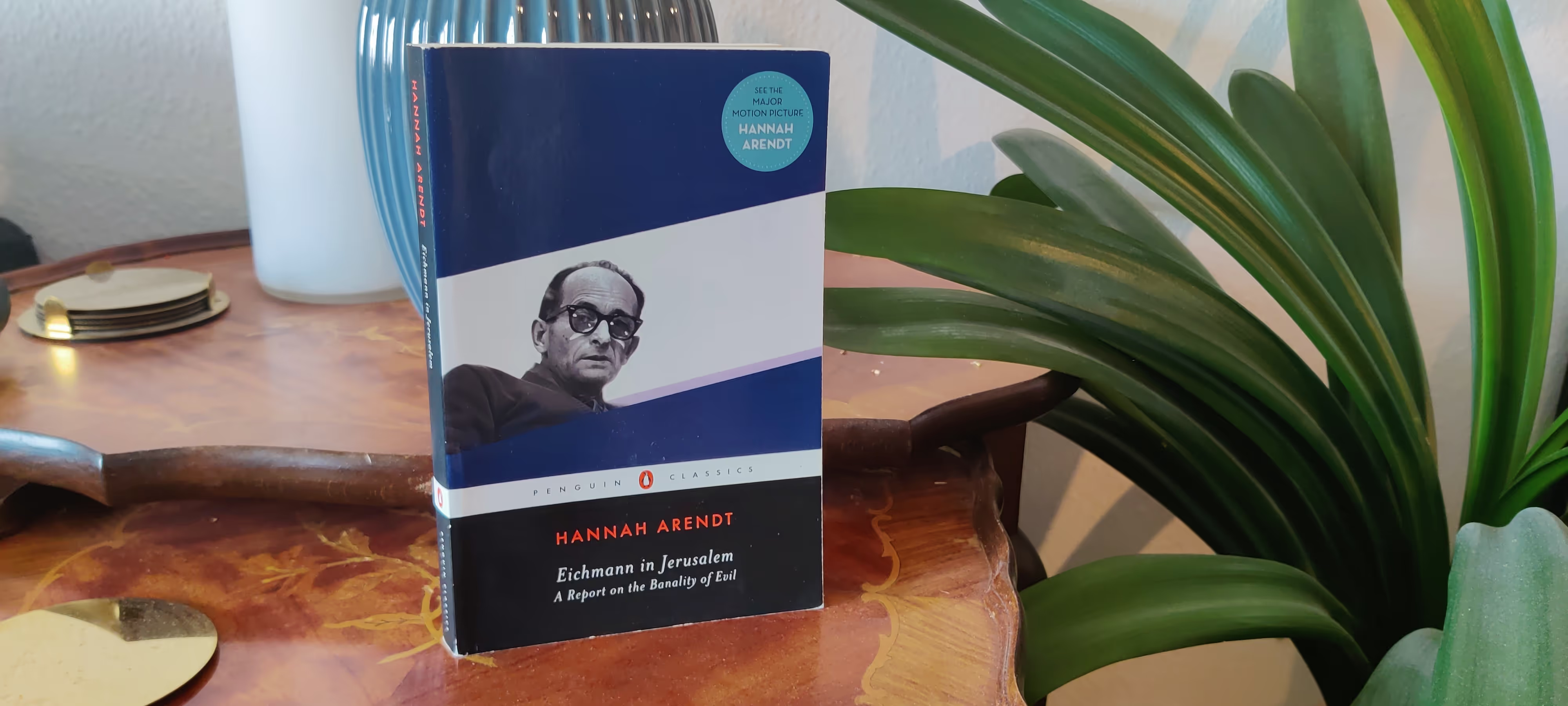

Arendt's Eichmann In Jerusalem.

(The following is an essay I wrote in January 2018. It reconciles the shocking revelation of Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann's starting normalism and how we can square abhorrent behaviors in our own stories)

Much has been said and written about the 1963 compilation of reporting by Hannah Arendt on the 1960 trial of former S.S. official Adolf Eichmann. Eichmann stood accused of sending thousands of Jews to their death during his time as the head of “Jewish Affairs” for the S.S.. Arendt’s account of the show trial put on by Ben-Gurion’s Israeli government probes the character of Eichmann as he recounts his version of events and the version of events the prosecution knows to be true. While they don’t contradict they also fail to make Eichmann out as the monster that the prosecution and the government desperately want. Instead Eichmann’s faults seem to be in his stupidity and arrogance. At least this is the man that Arendt depicted. Her subtitle to the book A Report on the Banality of Evil is the essential distillation of her report. Eichmann, while having done tremendous evil, came across as an uninspired bureaucrat doing his job as best he could. The ends of his actions were indeed malevolent but his depictions of his activities attempted to paint himself as a benevolent actor attempting to solve the ‘jewish question.’ The court ordered psychiatrists who examined him prior to trial famously said that he appeared more normal than they felt after his examinations. In fact, Eichmann’s own testimony is that of a man who seemed committed to the ideas of his own personal story. He did not come across as overly ideological, he repeated faught accusations of anti-semitism, nor did he come across as a particularly loyal devotee to Hitler and the Nazi cause. His devotions seem to be entirely towards himself. Arendt notes the many times in which Eichmann cannot remember the details of particular meetings he had or agreements that were decided in his presence. He can remember, however, all the events of his own story: his promotions, his setbacks, his failures.

Arendt paints the picture of a very real human being, a human being that is perhaps even more frightening than the picture the prosecution had been attempting to paint. Eichmann was a monster no doubt, but he’s a relatable monster. When at the end of our lives we look back, no doubt the most important memories will be the ones directly related to ourselves. No matter the excitement of our workspace or daily lives, the memories that will drill a hole in our brains are the ones closest related to what we think of ourselves. An idea that we came up with that either met success or failure is probably better remembered (or maybe more strongly remembered) than the successes of failures of our colleagues or outfits. Eichmann recalls in detail the three plans that he had for the settling of the ‘Jewish question.’ All three thwarted by forces outside his control: first the establishment of a protected state for Jews in an uninhabited portion of eastern Poland, second a protected state for Jews in Madagascar, and third a temporary holding for jews in an old fortress city in Czechia. The first two ideas never panned out (the second idea being entirely infeasible during the middle of a war) and the third idea was only implemented as a ‘show’ camp where prominent and elderly Jews were sent. Eichmann recalls the details of these three plans while also being unable to remember the discussions he was privy to which involved ‘The Final Solution’ of mass extermination that we now know as the Holocaust.

In Will Storr’s book The Unpersuadables: an Adventure with the Enemies of Science, Storr attempts to find the reasons why people fight so hard for ideas that appeal to themselves but have little or no actual evidence to support them. His journey takes him along with a leading creationist, on a week long retreat with a holocaust denier, and into the offices and houses of mystics, homeopaths and pseudo-scientists. He also delves into the brain and why people think what they think, particularly about themselves. Storr’s conclusion is that we all are the hero or victim of our own stories. In every narrative in our lives we attempt to find ourselves as either a hero, leading from the front and affecting genuine results, or the victim, stuck in unwinnable situations making the best of the opportunities afforded to us. Not only are we all capable of disregarding facts in the face of our own story, but we are also capable of remembering situations and moments in our lives as either fitting the heroic or of fitting victimhood.

Eichmann in Arendt’s description reminds me of the type of person that Storr describes in his book, the type of person we all are at some level or another. He repeatedly describes himself in his testimony as a victim of circumstances. He is a victim of having never finished school, of being the least capable of his sibling, of being fired from early work, and finally: of being overshadowed by other Nazi leaders as the ‘Jewish question’ became more consuming. His ability to also accurately describe his promotions and job successes fit the idea that we are all making ourselves the heroes of our own stories. Eichmann does not think of himself as a monster or a murderer, he describes himself as a dutiful official of the government, doing his best to implement orders from above and instil order to those below. At multiple junctures he mentions with pride the way in which matters were spoken of in his department. He takes pride in the ‘objectivity’ with which the ‘Jewish question’ was handled. He mentions that his department always used bureaucratic language and refrained from the emotional outbursts that other Nazi officials displayed.

It’s this normalization of monstrosity that is most concerning. Eichmann acted in a way that fit his story, his promotions, his failures. The reality is that the matters of the thousands of Jews he sent to their deaths were not his concern, his concern was with himself and his position. So too were the concerns of much of the Nazi hierarchy and Germany at large. The ways in which German society dealt with the aftermath of the war the atrocities they had helped implement was through rationalization and neglect. But can they be blamed for their rationalization? Can they be blamed for the complicity during the rise and fall of Hitler and his party? Probably not, while those like Eichmann surely deserve their fate, the peoples of Germany directly after the war were unable to look at themselves objectively. Nobody is capable of that. Eichmann was not so much the monster of malice and evil but the monster of human complicity and self-interest.