The quantification of everything, or how we forgot to think.

The last decade and half has seen the rapid expansion of the quantification industrial complex. Highly intertwined and previously uncountable statistics have been boiled down into systems which take black, white, and gray and give them numeric values. Making the complex into something tangible and quantifiable has given decision makers the ability to make more well informed decisions and to, ideally, keep personal bias out of their processes. The concept has gone from more numerically inclined fields and industries like finance and marketing to areas traditionally dominated by qualitative approaches like social science and sports.

This analytic revolution spilled over from Wall Street, where investors have been using complex numeric values to make decisions for decades. Starting in the late 70s, more advanced forms of data collection in baseball allowed decision makers to change their thinking about how to sign players, arrange salaries, trade for prospects, and ultimately win games. The author Michael Lewis wrote his 2003 book Moneyball, profiling one such prominent example in the 2002 Oakland A’s. The A’s turned one of the smallest budgets in professional baseball into a competitive club using advanced metrics which directed them to signing undervalued players. The success of the approach (and the book) led to nearly all Major League baseball clubs hiring dedicated analytics departments and even a 2011 movie starring Brad Pitt.

The concept quickly spread to other sports and to other countries. American football, traditionally considered a much harder sport to quantify, quickly developed a farm industry of startups and traditional media outlets which added their own metrics to the hard-nosed sport. Internationally, football (soccer) clubs began finding new ways to track player movement and to quantify their performance on the pitch beyond traditional statistics. In the NBA, the use of behavioral economics pioneered by psychologists Daniel Khaneman and Amos Tversky took human error out of decision making and left decisions up to consistent quantified systems.

In 2008, baseball writer Nate Silver took the analytics revolution to American politics. SIlver would create a polling aggregation blog in order to better quantify information about potential election outcomes. His blog would grow into an entire industry of election forecasts under the title FiveThirtyEight, named after the number of electors in the US electoral college.

In academia, particular fields which had traditionally been dominated by qualitative analyses have become increasingly quantitative. These changes to fields like history, political science, sociology, and anthropology have come as more traditionally easy quantitative fields have put pressure on the academy to be more scientific. In many respects, this pivoting to more quantitative research in certain fields has been welcomed. Reading tracts from leading political scientists of the mid-century will leave a modern reader wondering where they became so sure of many of their presumptions. The need to be more evidence oriented in the the messy fields which deal with human behavior and group dynamics is probably a good thing. However, the quantification of all things academic has also come increasingly as a response to so-called “hard scientists” in mathematics, physics, biology, and environmental sciences where quantification is more readily equipped to explain those worlds.

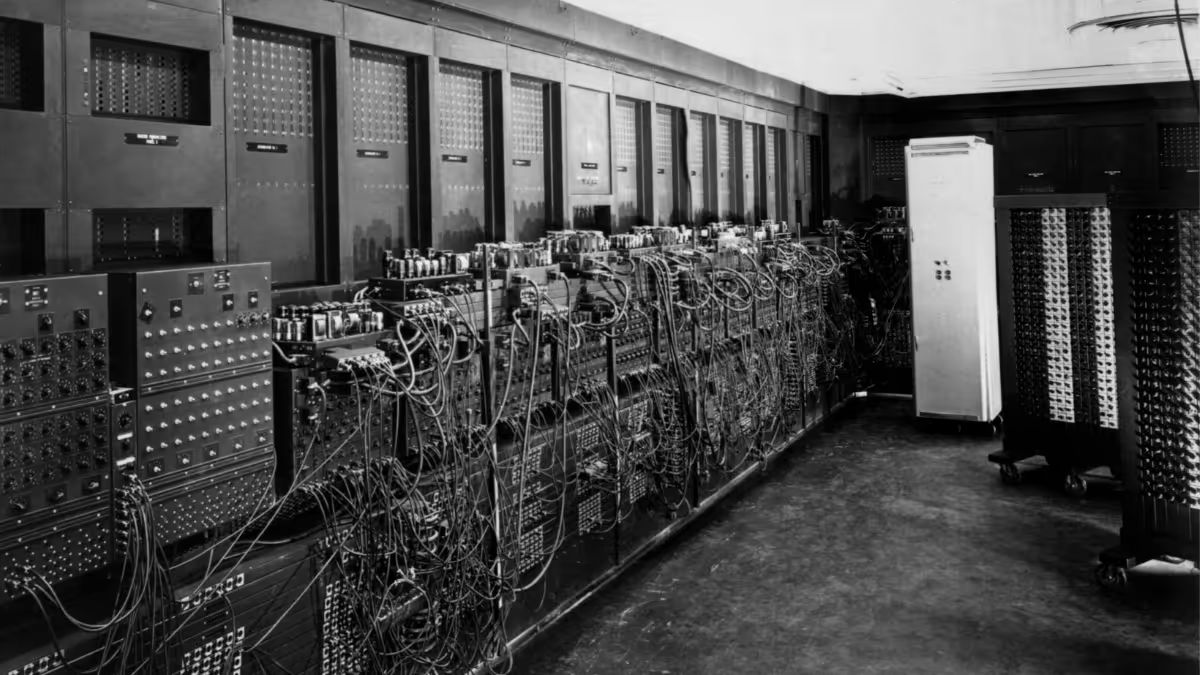

Our drive to quantify all things has corresponded with, and no doubt been contributed to by the extreme growth of personal computing and digital technology. The percentage of smart phone users in the world is estimated to be 83%, which means 6.6 billion humans are currently equipped with machinery that allows them to easily access vast troves of information, record audio and video for posterity, and interact with a myriad of other human beings. Computers are, as their root-word suggests, a tool used to compute numbers and data. The incredibly quick rise of the computer (to which the smartphone has become the most common form) has brought about a way of thinking of the world through means a computer can only understand. Quantifying interactions and producing systems to understand complex phenomena are what we use computers for, it’s what they are designed to accomplish. Could our drive to quantification have to do with the rapid spread of the personal computer and the incentives to understand how they work and how we can make them work for us?

In 1985, media critic Neil Postman released his most quoted work Amusing Ourselves to Death. The book centered on Postman’s critique of television as a medium which was warping the human mind. His thesis has been belittled as little more than modern Ludditism (the 19th century textile workers who destroyed machinery which they deemed to be encroaching on their labor), while those who took his argument seriously proposed that the proper response would be to create more meaningful, enriching television. But what is lost by both proponents and critics of Amusing Ourselves to Death is Postman’s sincere belief that it was the medium not the message which mattered most. No amount of enriching, intellectual or educational television can overcome the necessary structure of television: the content must be engaging, immobilising, and entertaining.

The medium is the message for the modern quantification industrial complex. Nearly everyone uses computers in their daily life and certainly work. Because computers are devices for quantification our desire to quantify and create numeric codes for the unnumbered is an ever present pressure. Quantification is the manifestation of our reliance and usage of personal computers. We compute because the primary medium for our work does computing best.

The computer is obviously only a piece of the quantification puzzle. If we were not using programs and apps on our computers most of us, myself very much included, would have little patience for the obtuse world of binary and code. It’s those programs, apps and websites who manifest the quantifiable desire of our devices into the realm of human interaction and behavior. The brilliance of the social media platform was its ability to take human interaction and put an easy, trake-able number on it. How many likes has this post garnered? How many times has your video been shared? Seen? Commented on? The computer, well equipped for this sort of game, counts the records, stores the data, and passes that information on to the user and developer. With that information, the human interface behind these apps and sites can decide what forms of quantification deserve greater reward. Are likes more important than shares or comments? Certainly not. The structure of the major platforms is to push content which receives high engagement (as measured via the data of likes, shares and comments) in order to maximize their own most important quantified information: how long users remain on the site, browsing, commenting, and sharing content. This, in turn, is spurred on by the quantified decision making of other businesses who, wanting to be seen by the most possible consumers, rely on the platforms as a means of advertising.

Quantification online, particularly on major platforms like Google and Facebook, goes further than just basic engagement information. These platforms also engage in creating user profiles so that they can better target advertisements towards their mostly unwitting products. Distilling the complexity of human existence into a host of traits and characteristics that are likely to consume using previously measured behaviors.

Which leads us to what must be the root catalyst for our quantification revolution, the market. Buying and selling is almost indelibly tied to quantification. Basic goods can be counted, they are traded for set but moving prices dependent on the whims of the collective consumer we call the market. I bought a coffee this morning for 36 Danish Kroner, a price I’m willing to pay based on the form of quantification I currently reside in. Transfer that price to dollars (around $5) and I may feel less thirsty. As we move through the capitalistic world, deciding what we want to pay for and what we must pay for, we are constantly calculating those numbers against our own income and current balance sheet. In many ways, the constant pressure to survive in the modern world is located in our ability to compute our income vs our expenditures. Do I have enough X to survive today? Will I have enough tomorrow?

The human computer then is an outgrowth of our capitalistic success. The ability to hunt, fish, gather resources, build rudimentary shelter, start a fire have little to do with quantification. But moving away from those primordial systems of survival to our modern one and you have a world where quantification becomes the absolute primary skill of survival. Can I afford that scone? How much time do I have to get to work? Is my credit score good enough to take a loan out on this house? It’s perhaps no surprise we seek the quantification of everything, we’ve learned to believe our very survival depends on it.

Philosophically of our quantified age comes in the form of the scientific revolution, which ushered in our modern understanding of the world as a collection of explainable phenomena. The easiest realm and the earliest spaces for the scientific revolution included the study of the stars and the universe outside our own planet. Falling from the stars, scientists directed their attention towards other species, geological formations, weather patterns, the rules governing motion, medicine, and shamefully the supposed hierarchy of races among humankind. Today’s quantification is in no small part the outgrowth of the developments of the 16th, and 17th century empiricists.

We call many of the fields inaugurated by these early scientists the hard sciences today because their quantifiability is so clearly possible. Measuring the length of various frogs, or the temperature of various sublayers of the Earth are easy once we all accept universal measurements for length or temperature. The reliability of physics allows for crafty scientists and mathematicians to compute how and why objects move and react to each other in the ways they do. This quantification is both useful, and more importantly, reliable! The strength of quantification in the hard sciences is the replicability of those measurements. As long as conditions remain constant, we can know for certain just how far a ball will travel when pushed with a consistent force.

Where quantification becomes more difficult is when we attempt to apply it’s clear benefits to scenarios lacking clear and agreed measures. The fields of inquiry which study complex human interactions, systems created out of whole cloth, or cultural practices lack the clearly marked indications of measurability. How do you measure the impact of a political interest group? What is the measure of language? Can emotion be accurately measured for intensity? What about the outward affect one’s emotion has on the social circumstances they inhabit?

Social scientists do their best to come up with measures for questions like these but they will always lack the ease of understanding which the hard sciences benefit from. A mathematician may fudge the numbers but they can be assured that, if they get it right, their answers will be replicable and correct. A social scientist must always combat the messy reality of human existence. Clean experiments taking place on a blank slate are not possible, neither practically or ethically. Therefore, social scientists must rely on controlling for factors they believe may affect their measurements. In doing so, they must enact judgements which the hard sciences can feel far more confident about in their own work.

The critique of the social sciences from certain members of the hard sciences have come in the form of open critique as well as hoaxes used to highlight the perceived unscientific nature of social academia. However, what these critiques and attempts to embarrass invariably miss is the messy and complicated reality of human existence. It may simply be true that not all phenomena are measurable in the same way that we can consistently weigh a piece of metal or measure the degree of an angle. The systems of quantification which have infected every facet of our lives has made quantification out to be the only acceptable mode or reality? But is that really true?

Fundamentally, phenomenon is measurable because we agree upon a common measurement. Our inability to agree on the common measurement of a social interaction or the effect of social pressure does not necessarily mean that these phenomena lack a mode of study, rather, we need to retrain our brains to think and study phenomena from a qualitative perspective. Perhaps retraining isn’t even necessary. Our brains are already fine tuned to qualitative thinking. The early hunter-gatherer whose lifestyle our brains evolved to complement cared little for the measurability of the phenomena around them. Rather, the ability to messily judge threat from pleasure, friend from foe, and rival from lover were far more important to their survival. Then maybe our goal should be to accept that qualitative study is a necessary, and equal form of thought. Not all phenomena must be measured or quantified in order to find an empirical reality.

The quantification of everything is not an inevitable process and it does not have the monopoly on truth or reality. Our ability as human beings to view complexity and not shudder or run for a reliable measurement is the reason we have been able to conquer our planet and create ever increasing bonds of social trust. There is no doubt that the quantification of everything has led to wonderful advances in human well-being and technology. But we also must realize that the quantification of everything threatens to take away our most basic mental systems, the systems that have traditionally promoted human survival. Neither form of inquiry is useful without the other. I don’t expect the quantification industrial complex to wane anytime soon, I just hope we remember to bring qualitative thought along for the ride. Not as an inferior product of our evolution, but as a necessary partner in the pursuit for truth.